Given that Kew Gardens is home to the world’s most diverse collection of plants and fungi – studied from countless angles and for countless purposes – it begs the question why it has taken until now for a dedicated exhibition on the crossover between plants and fashion to be staged. The “now”, however – as in the Material World exhibition, running from 20 September to 2 November 2025 – is worth every bit of attention.

Perhaps it’s the zeitgeist. The last few years have seen an undeniable surge of interest in plant-based textiles. New, innovative fabrics are being developed; ancient fibres are being rediscovered as low-impact alternatives; and traditional knitting, weaving and dyeing techniques are re-emerging as celebrated craftsmanship. At the same time, consumers are losing trust in both ultra-fast and luxury fashion, as reports of alarmingly similar abuses and omissions emerge from both sectors.

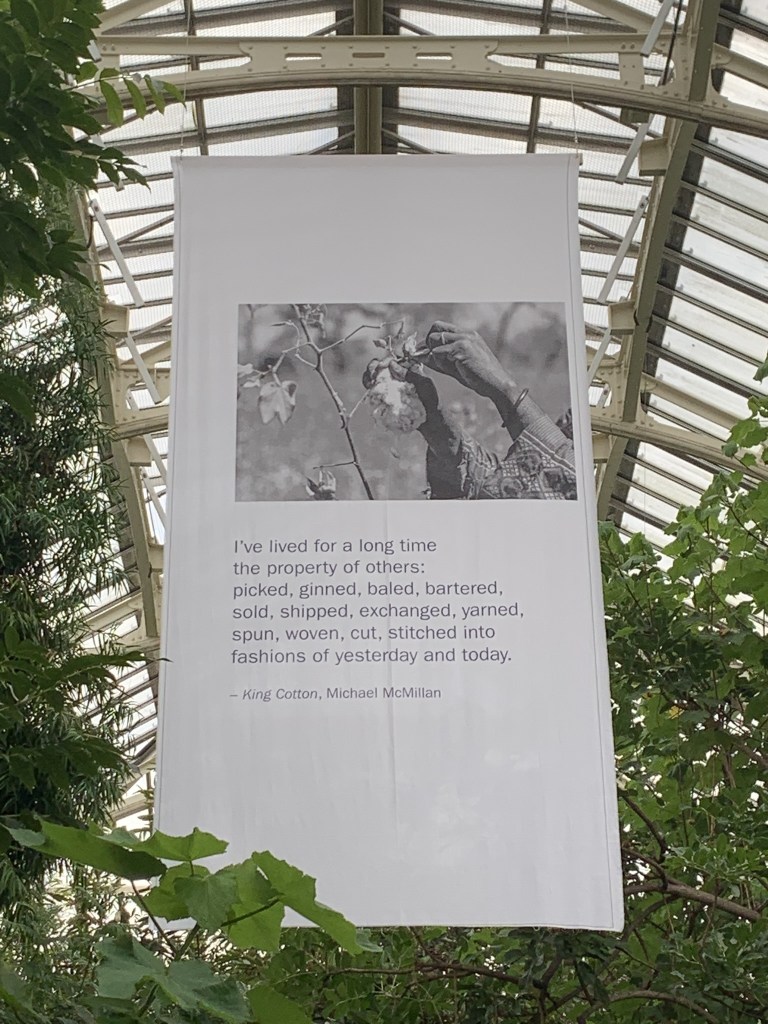

Running in tandem with Sustainable Fashion Week – held across 34 UK locations – and the inaugural London Textile Month, Kew has placed a strong emphasis on traceability and ethics. Michael McMillan’s audio artwork How Cotton Became King, created with Dubmorphology and Rowland Sutherland and purposefully located in the Africa section of the Temperate House, tells a story as raw and harrowing as the reality it represents: the hidden history behind the rise of cotton as the world’s most popular fibre from the 18th century onwards.

“We know about Eli Whitney’s cotton gin, Richard Arkwright’s spinning machine, and how Manchester became Cottonopolis. But nothing about the slaves and workers who produced the precious commodity.”

Unmarked Graves, Michael McMillan

by Michael McMillan

And while the resource-intensive nature of cotton is no is no revelation to textile circles, yet the story of slavery, colonialism and capitalist exploitation cannot fail to move – especially in light of the Transparentem report, published in January 2025, which revealed ongoing abuses – yes, children included – in today’s supposedly trusted cotton supply chains. It begs the question whether humanity has truly progressed to a more civilised level. Sadly, the answer is hardly yes. As long as abuse persists, we cannot afford to forget the darkest parts of history.

“I’ve been beaten on rocks, and hand-washed in Dolly Blue, spun in machines, even dry-cleaned too.”

King Cotton, Michael McMillan

The search for low-impact fibres and ethical approaches leads inevitably to craftsmanship.This turn towards craft – and therefore holistic stewardship – is hardly a trend. It is damage control, rooted in the awareness that humanity is not going to consume less. Instead, it offers an alternative path: one that supports livelihoods and leaves a lighter impact on the planet, rather than perpetuating cycles of exploitation. Our readers are no strangers to the idea of fashion carrying memory. But to hear the voices of artisans and farmers from Colombia, India and Peru – those who plant, water, harvest and knit in rhythm with nature – sharing stories of fibres that hold centuries of indigenous practice, brought together by the League of Artisans and its founders Sol Marinucci, Dr Ritu Sethi and Carry Somers, makes one look twice at the clothes we wear, and begin to ask: where else might histories be found – or omitted?

by Kate Turnbull, Carry Somers, and Becca Smith

by Kate Turnbull, Carry Somers, and Becca Smith

Threads of the Canopy, a textile map of Kew’s trees was created by natural dye specialist Kate Turnbull, artist Becca Smith, and Carry Somers working with Kew’s Youth Forum and participants in Community Open Week. It is both a tribute to the trees and to the essence of craftsmanship: people coming together to bear witness through making, using naturally dyed embroidery threads, tree-based printing inks and hand-carved blocks.

Artistic installations by Nnenna Okore (Between Earth and Sky) and Lottie Delamain (Global Threads) are as visually engaging as they are technically thoughtful. Okore’s wing-like forms, crafted from biodegradable materials, soar yet remain suspended – literally between floor and ceiling – in the oldest surviving Victorian glasshouse, urging viewers to pause, look up, and wonder about the place, purpose and ultimately the fate of everything we produce and consume. Delamain’s newly planted garden offers a striking contrast: four beds of dye and fibre plants from across the world, juxtaposed with giant pot-like structures made from waste textiles and scraps that physically enclose the beds. There is also a “cheat sheet” of the 54 plants Delamain used in the beds – complete with images and names – for those tempted to reproduce some at home.

Jessie Von Curry presented Hyphal Body – a sculptural T-shirt made from mycelium grown on hemp waste, reflecting on how fungal networks sustain entire ecosystems, including those in which humans live – and exploit.

And it is not only the established names. Five students from London College of Fashion (UAL), presented experimental work in both form and material, using pineapple and lotus fibres, nettles, seaweed, herbs and fungi and many other materials. Their titles alone form a manifesto: Regenerative Knitwear (Silvia Acién), Afterlife Series (Beth Williams), Healing Puffers and Plant Leather Garments (Eirrin Hayhow), and Woven Kinships (Jessie Von Curry and Vega Hertel). Together, they call for a renewed understanding that the lives of plants and humans should never have been considered separate in the first place. If the earlier displays invited reflection, this section delivers excitement – not only about the works themselves, but also about the future, where the next generation of fashion creators are as committed as they are inventive.

Global Threads by Lottie Delamain – panels installed over the plant beds.

And while we wholeheartedly agree with Kew Gardens’ motto emblazoned at the entrance – Our Future is Botanic – it is clear that a sound understanding of the past, with both its heritage and its shadows, is essential to shaping that future. With this exhibition, and an impressive programme of the After Hours series of performances, poetry readings and hands-on workshops, Kew Gardens has achieved something rare: creating an uncanny cabinet de curiosities of plant-based works that ignite curiosity far beyond the fashion world. And that is a significant win.

***

The Material World runs from 20 September to 2 November 2025 at the Temperate House, Kew Gardens.

Full schedule of events available at Kew’s official website.